Designing Better Game Economies

A foundational approach to designing an in-game economy

We’ve seen more games crash and burn in the NFT space than games succeeding as the P2E crowd championing sustainable yields has evaporated. Sadly, or gratefully, there is nothing that all the high-end tools, polished via dev crunch and the gaming engine can fix if the underlying economy design has been built on an unsustainable foundation.

My name is Boffin and apart from loving a great story, which is why I started Artist Spotlight, my background is in behavioural economics. I’ve also always had a passion for games as an experimental medium and combing the two affords me a unique insight into certain topics. There is a lot to be learnt from game design and this post will explore that topic in pursuit of outlining sustainable in-game economies.

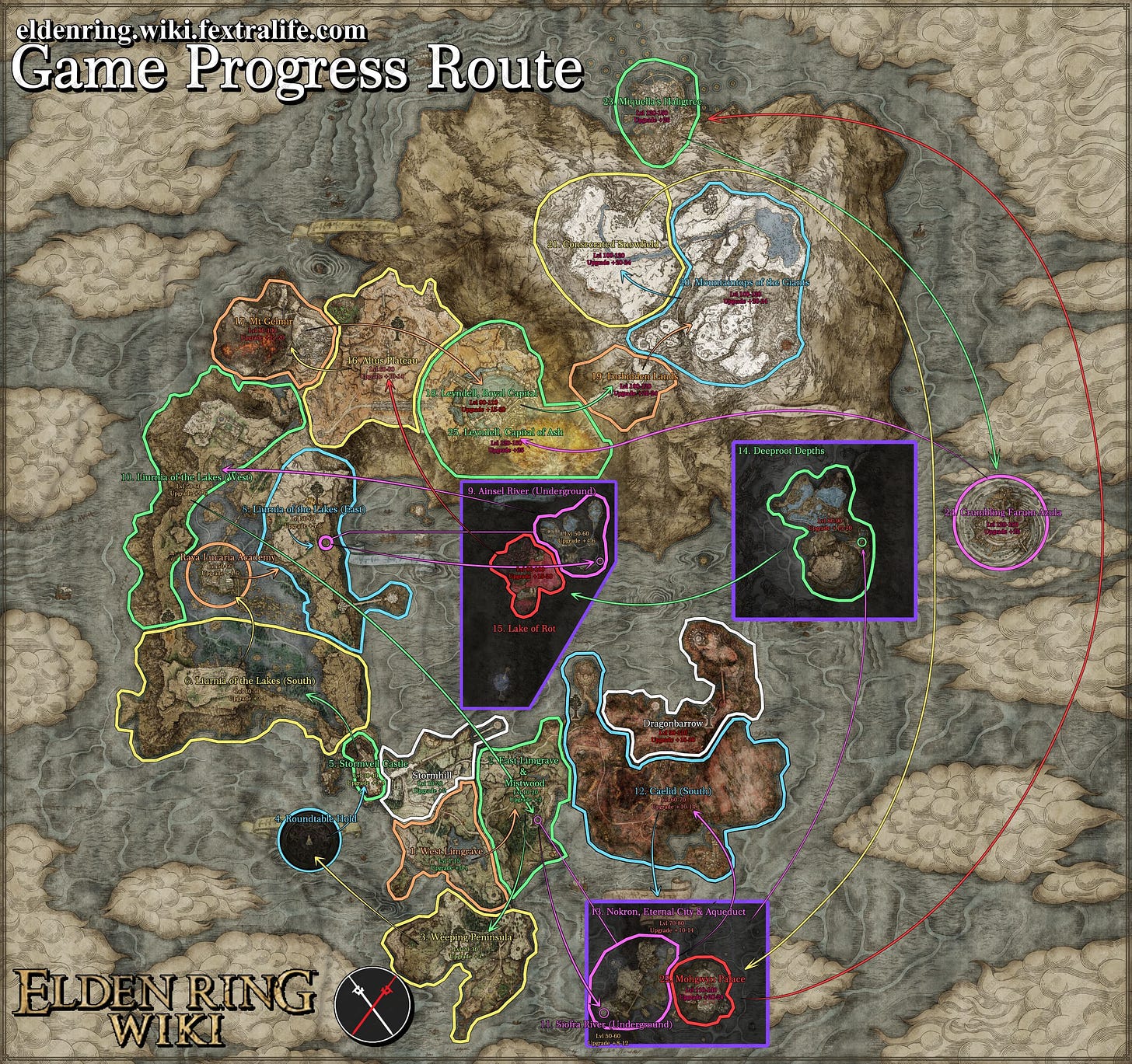

Seeing that P2E is an extension of game economies, with the blockchain acting as a mechanism for maintaining the economic aspect, we can take inspiration from video games (Triple-A to indie) and look into not only how they design their economies but also how they have multiple tools at their disposal to create a cohesive and thriving economy.

Video game economies can be quite complicated to design, if done wrong it can lead to imbalance and at the worst end exploits. If we add a layer of “blockchain” to the mix, this can lead to debilitating losses and even kill the entire project. A game to do this in a very public way is none other than Pegaxy. During its peak, it was hailed as the “Improved Systems Axie Killer” with both currencies PGX and VIS soaring in value but looking at both prices today paints an entirely different picture.

However, if you get it right, it’s an invaluable tool that can affect a lot of things, like shaping player behaviour and offering meaningful choices while creating a different kind of puzzle to be solved. There has to be a sustainable model rather than the inflation-fest games we’ve seen that are relentlessly bot-farmed to death.

This post aims to provide a crash course on how to create an in-game economy. This won’t be applicable to every game out there but a variation of these pillars will be found in all in-game economies. While it’s evident that blockchain/NFT projects have the technology and manpower to create these economies which are globally accessible via mobile phones ultimately facilitated by the blockchain, the actual design of the economy in its current implementation is shoddy at best and a disaster at worst. So, Let’s take a step back and start by answering a simple question:

What even is an economy?

An economy can be described as a flow of resources that move around the system.

What are resources?

The resources in question can include anything from ammo, crafting material, experience points (XP) and even money. Every game that exists has its own unique economy and most of them share the same building blocks of an economy broken down into five distinct pillars:

The Faucet

The Inventory

The Converter

The Sink

The Trader

The Faucet

A faucet generates new resources in the economy. This can mean enemies for XP, rocks that give you iron ore or even a regenerating health bar. These can also be generated either automatically (regenerative healthbar in Call of Duty) or manually if further action is needed by the player (mining in Minecraft, farming enemies in MMOs). We can use faucets to incentivise certain player behaviours. If we want a player to fight enemies, we can attach loot once they’ve exterminated them. If we want the overarching world to be discovered, then you can make region-specific materials needed for crafting items required to advance further.

Just like a faucet operates in real life, we can also dynamically change the flow of resources to make certain resources more common or rare compared to others. This can mean that there is an influx of resources at the start but as the player progresses, you lower the supply so the player begins exploring more as the effort/time needed to progress in the same area is higher than exploring the new area with “richer” resources. It's also important to note that a broken faucet will completely decimate an economy. In blockchain games, the faucet is widely known as inflation through token emissions dripping at unsustainable rates leading to the aforementioned bot-farms and inflationary downfalls that we’ve seen with Pegaxy and Axie.

The Inventory

This holds the resources that the player gathers/owns. An inventory can be an actual inventory which holds different types of items or it can be represented by a counter (such as a coin wallet). What's important here is the determination of some form of a limit on said inventory. This can mean giving the players a maximum weighting of items that they can carry or forcing them to fit the items in a “backpack” style mini-game, adding another layer of complexity to the overarching game.

![How 'Resident Evil 4' Perfected the Inventory System [Resident Evil at 25] - Bloody Disgusting How 'Resident Evil 4' Perfected the Inventory System [Resident Evil at 25] - Bloody Disgusting](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!L0As!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fbucketeer-e05bbc84-baa3-437e-9518-adb32be77984.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F09209ede-41c5-45a7-8547-2f46c471cefb_740x412.jpeg)

This again nudges the player into thinking about what is useful at any given time rather than stockpiling everything until the very end. You know, make them actually play the game. This system however needs further refinement in a blockchain setting. If everything is a token that is easily tradeable in and out of the game via DEX’s, then you will have some players that will buy everything they need to without the need to play the game. This creates obvious misaligned incentives as value is constantly extracted and enhances the risk of alienating longterm players. If the game is completely devoid of any blockchain transactions being necessary, then the “blockchain” part is simply a marketing gimmick that we’ve learned through public perception further alienates the legacy gaming community. Games need an inventory system that not only makes sense inside of the game but also utilizes the blockchain which, as it stands, very few games incorporate correctly throughout the space.

The Converter

A converter, as the name states, changes one resource into another. This is one way we remove the resources that enter the economy via the Faucets. Some resources in the economy are useful in the state you get them (like ammo, health, money) but others on their own will not be useful. In some games, the conversion rate will have a direct impact on the pacing of the game.

If we know how many XP we need to level up and we also know how many XP is roughly dropped by enemies, then we can work out how many enemies the player needs to slay to level up. We can then either speed up the gameplay or slow it down by either increasing the XP limits or lowering the XP dropped by enemies.

Convertors are yet another tool that is used to encourage player decision-making. Whenever a shop is visited, the player needs to make a choice on how to best spend the collected coins they have on what they think will help them in the next leg of their journey. To design a compelling converter there has to be some level of tradeoff for the player.

If your economy has six different resources and each resource levels up its own area exclusively (armour, damage, mana, etc.), then the only decision the player makes is how long they need to farm that specific area until moving onto the next region for the next power-up. However, if you only have two resources in the entire game and they’re needed to craft everything from armour, health and weapon upgrades, then a tradeoff needs to be considered.

While the player can still “farm” these items, we can adjust the faucets to make these crafting supplies rarer as the game progresses through limiting faucet resources the longer the game progresses. As we’ve previously discussed, having several currencies can be a good incentive for exploration but if you’re targeting player agency then having fewer resources is more beneficial.

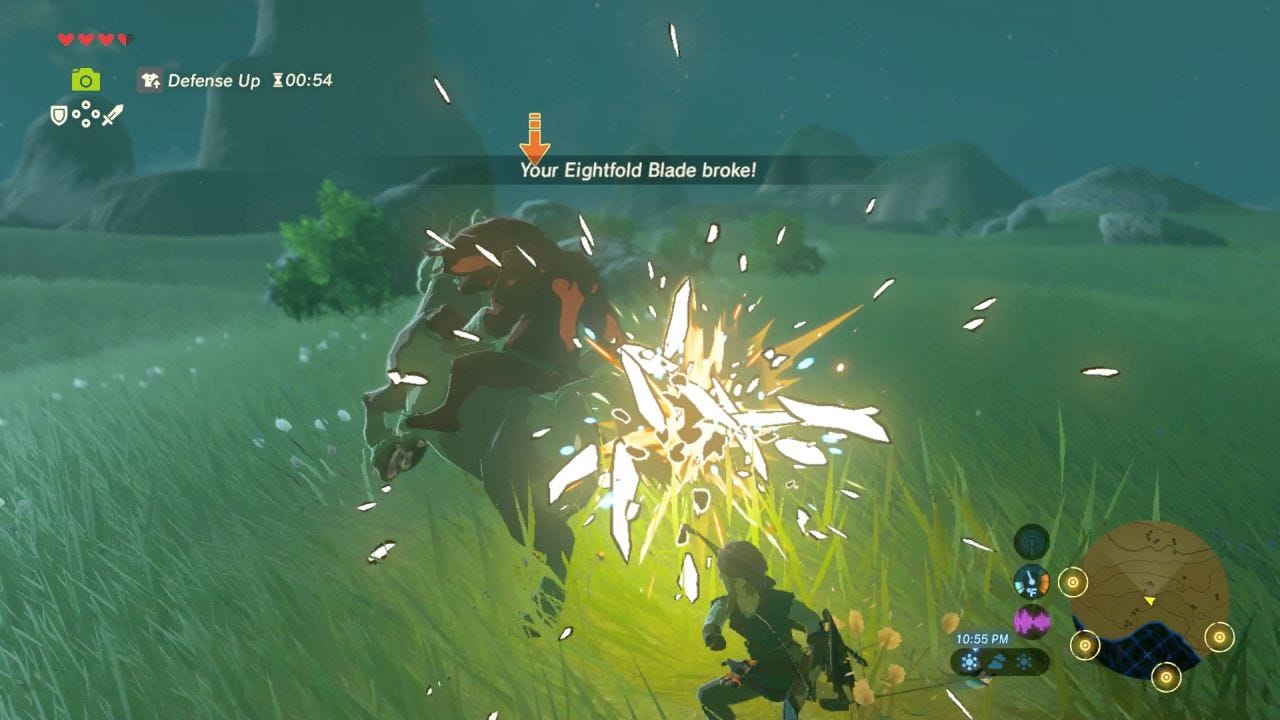

The Sink

With the exact opposite function of a faucet, the sink permanently removes resources from the economy. Ammo count depleting every time you use a weapon, the efficiency of tools lessoning for every block mined, and health points being reduced for damage the player takes are all examples of sinks. The key difference between the Sink and Converter is that rather than allowing players to return to the faucet with “an upgrade”, the sink will return the player to the faucet with nothing as they’re replacing the items that were lost. To put it into simpler words, the sink works as a “tax” for playing the game, which increases the game and the economy’s complexity.

The Sink slows the player's growth as it becomes nonlinear. However, a sink can be used for other purposes such as encouraging the player to try new strategies in their resource gathering that can push them to new limits as players are negatively impacted if they stay in one place for too long. Another common game sink which is found in survival games would be the “Hunger Meter”. A hunger meter forces players to explore to look for food, which doesn’t “add” to anything they’re doing but results in consequences if ignored. The sink is the perfect way to add risk to the game as a whole.

The Trader

A trader buys and sells resources with their own agency. In “traditional” game economies, this is one of the rarer pillars to have in the game but they add an entirely new level of complexity to the game (and this is the only pillar that most developers singularly focus on in their blockchain games). A trader can be a shop in a single-player game, but in multiplayer instances, they have their own inventory and resources which they will value differently. As such, it’s possible through the player's ingenuity to buy an item for “cheap” through multiple trades with various traders.

We can reward players with a “profit” for making successful investments and figuring out the trade puzzles. Traders are another design mechanic by which we add risk and reward through means that the players don’t directly control. If they understand and decipher the puzzle at hand, they can profit handsomely but if not, they’ll end up losing their resources or worse, losing the game entirely.

As trading has its own intricacies in single-player games, opening that up to a multiplayer game would be its own beast to conquer. Players can speculate on what’s desirable, they can flood the market with a specific item lowering its price or even try to corner the market owning the means of production for certain items; it’s limitless. Trading mechanisms are also one of the hardest possible economies to maintain as companies like CCP Game (Creators of Eve Online) and Valve (Creators of CS:GO, Dota 2 & TF2) hire economists to balance their game economies.

Fun fact, the lead in-game economist who joined Valve in 2012 (around the time TF2 was thriving and CS:GO had yet to launch its skin market) Yanis Varoufakis was actually tapped to be the Finance Minister of Greece in 2014.

“Multiplayer” trading games (ranging from MMOs to player lead economies such as TF2 and Warframe) are vastly more complex, and it’s definitely out of the scope of this article (but they’re fascinating in their own right).

How do all these systems work together? Well, I’m glad you asked hypothetical reader. Here is a quick graphic to show how these pillars work with each other:

As it should be evident by now, you can’t design a “trading economy” without also ensuring the other interlocking part of the game economy is just as well thought out. What we’re mostly seeing in blockchain games is the means of trading being worked on rather than the economy as a whole which is why they’ve failed to date through the exploitation of token emissions.

If you’re a game designer in this space, this should be right up your alley. If you’re a player/investor then you can use the concepts here to assess how sustainable the economy, and by extension, the game, is before investing your money, effort and time.

If you are interested in further economy design for games, then these posts go into a lot more detail over the concepts explained above:

If you’ve made it this far, thank you for reading this and I hope this has been a useful read. You can follow me on Twitter and let me know what you thought about this article and don’t forget to subscribe to Page One for your essential crypto readings.

Really enjoyed this write up. Great examples included here.